How Databases Are Used to Trace Guns and Track Mass Shootings in the U.S.

Outdated platforms, data quality, and access must be fixed in the urgent effort to stop the bleeding

To address the epidemic of gun violence in the U.S., we need to understand it. And for that, we need not just gun reform, but better data.

The tragic massacre of 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, has renewed the long-running debate about how to prevent these terrible acts of violence.

Gun reform is a contentious issue in the U.S., but progress is possible if policy is well informed by insightful data that can lessen the rhetoric and point to solutions.

The feds have their hands tied when it comes to tracing gun ownership. Federal law (specifically, the Firearms Owners Protection Act) prohibits the establishment of a centralized database of gun owners.

The answer isn’t one big centralized database for gun control, that much we know. However, there are a growing number of open, public sources, such as the K-12 School Shooting Database, that shed light on this urgent situation.

From the perspective of modern data management, many of these data-tracking efforts are rudimentary and outdated, and data quality is an issue. There’s an obvious opportunity to bring best practices into data collection, curation, and sharing.

ATF’s eTrace

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives’ eTrace database has its role, but it’s an antiquated system with restricted use. eTrace keeps a record of the purchase history of millions of firearms from manufacturer to retailer to original gun purchaser.

It’s used to help solve gun-related crimes by tracing serial numbers back to the original point of purchase, providing investigators with potential leads. According to ATF, more than a half-million trace requests were processed in FY 2021.

But eTrace is virtually useless in preventing the kind of worst-case scenario that happened in Uvalde — the legal purchase of an AR-15-style semiautomatic weapon and high-capacity magazines by a hell-bent teenager with no criminal record.

In fact, eTrace is designed to be opaque, in the sense that the system cannot be searched electronically. I visited ATF headquarters in March 2013, a few months after the devastating school shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, in which 20 children and six staff were killed.

Here’s my report at the time, “ATF’s Gun Tracing System Is a Dud.” And an op-ed I wrote for the Christian Science Monitor.

To get a sense of just how old-fashioned the ATF system is, take a few minutes to watch this documentary-style video. If you’re a data practitioner, you’ll be shocked and amazed at the sheer magnitude of this never-ending digitization project.

K-12 School Shooting Database

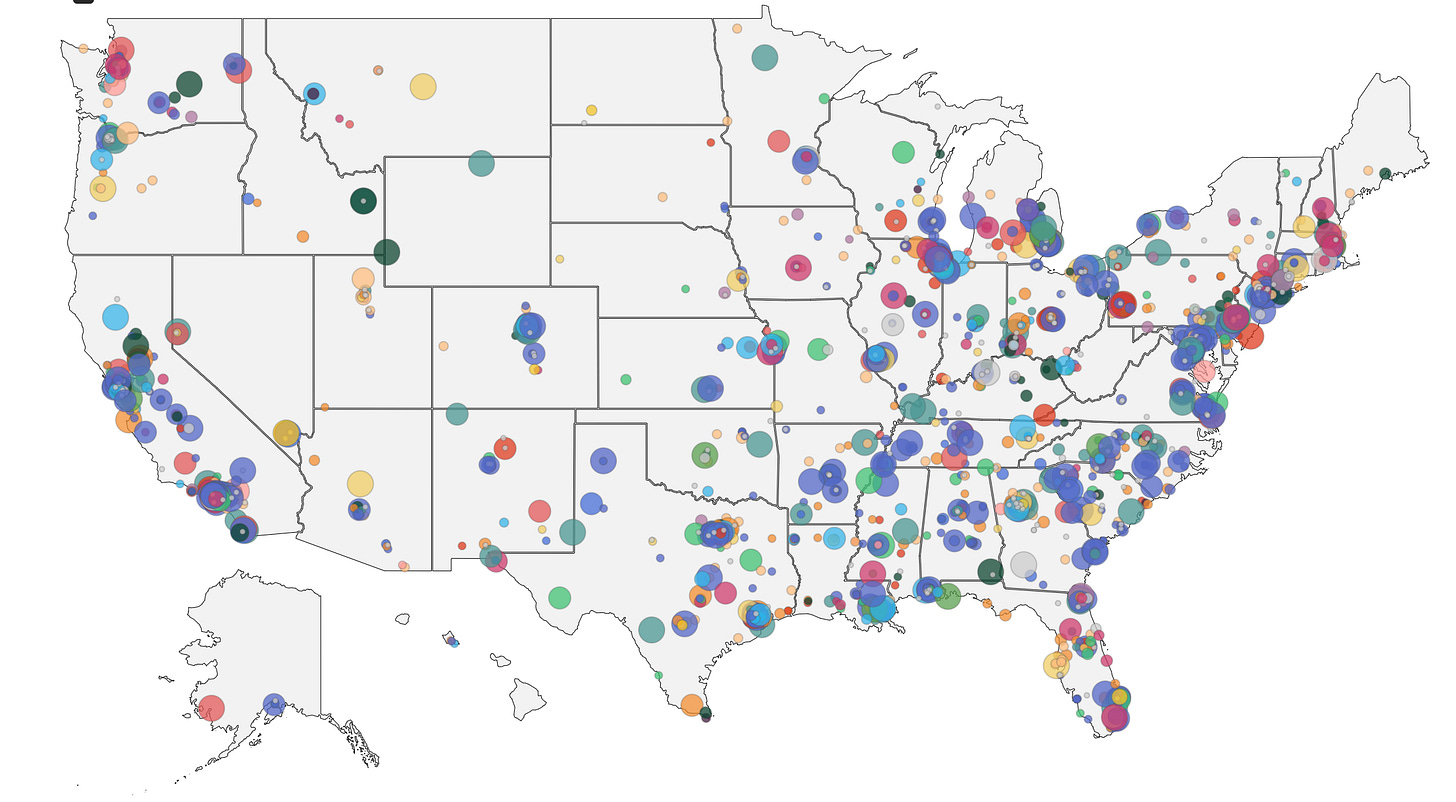

Public-sourced data opens the aperture on gun violence. The K-12 School Shooting Database, which started as a research project, compiles data from more than 25 sources, including government reports, media, and crowd-sourcing.

The database has an interactive map that can be filtered by situation (i.e. escalation, drive-by, self-defense, bullying, etc.); type of school & location (classroom, parking lot, and so on); type of weapon and outcomes.

There are also graphs and charts that illustrate active shooter vs. non-active shooter; killed and wounded; the shooter’s affiliation with the school; and more.

You can view the K-12 School Shooting Database, and download the dataset, here.

An article in Florida Today includes an interview with David Riedman, a PhD student at the University of Central Florida, who created the database with colleague Desmond O’Neill.

"This is not a problem that is new,” Riedman said, in the wake of the Uvalde shootings. “It’s not a problem that relates to the internet or social media or violent video games or violent movies ... it’s a much deeper, generational issue."

FBI Background Checks

The FBI conducts firearm background checks through the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, a 24-hour online service.

As of April 2022, NICS contained 26.2 million active records in its indices. The FBI processed 28.3 million background checks for firearm permits or purchases in 2019, the most recent year reported. Of those requests, 103,592 were denied.

The chart below shows reasons for denials over the past 19 years (“PTD” stands for Program to Date). Note that adjudicated mental health accounts for less than 3% of denials over that span, an interesting data point amid speculation about the mental state of mass shooters and the screening process.

Other sources

There are many other sources of info, including both media and grassroots. Following is just a partial list:

Mother Jones, an independent media organization, recently updated its “U.S. Mass Shootings” database, which covers incidents over 40 years, from 1982 - 2022. The data is downloadable in CSV format.

Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts, says that 19 states and the District of Columbia have instituted red flag laws, which allow acquaintances or the police to petition the courts to revoke firearms from someone deemed a serious risk. This Stateline chart shows states with red flag laws.

The Washington Post has a schools shooting database, as well. Unfortunately, it’s paywalled. The Post would do well to open it up for the global effort to understand and move things in the right direction.

The Gun Violence Archive tracks deaths and injuries from guns, including suicides, victims under age 12, and accidental.

This article by Above the Law includes a long list of schools that have experienced shooting deaths. (It’s unstructured data, not easily consumed or reused.)

The Violence Project’s Mass Shooter Database.

Skepticism about the data

Not everyone is in favor of all of this data-gathering or the way it’s sometimes used. As Fox News reports, “Gun rights group’s ATF report accuses agency of making ‘illegal gun registry.’”

And The Trace, a news org focused on gun violence, reports that “The NYPD is Tracking Possible Shooters in a Secret New Database.”

The Center Square, a website of state and local government reporting, recently published an article headlined, “Tracking School Shootings Not a Science,” which questions the categorization of some data, and how that affects our overall understanding of the trends.

So, data collection and sharing must be done carefully, responsibly, and within the law, with all of the attention to access, privacy, security, and governance that is the standard (if not the norm) in other data environments.

But that’s a call to action, not reason for delay. Modern data platforms and best practices have a vital role to play in identifying risks and developing countermeasures to gun violence, and ultimately saving lives.